|

The Story of the

Mountain

Mount Saint

Mary's College and Seminary

Mary E. Meline & Edward F.X. McSween

Published by the Emmitsburg Chronicle, 1911

Chapter 54 |

Chapter Index

Chapter 55: 1870-1872

On Commencement Day, 1870, the roll

counted one hundred and twenty-two

boys and twenty-eight seminarians.

There were four graduates among them,

two who afterwards reached distinction

in the faculty, Michael Haves and John

O'Brien. Reginald Jenkins took the

honors of the graduating class and the

valedictory. The other honor men were

Henry Churchill Semple, Thomas J.

McTighe, John B. Head, James

McCullough, Joseph G. Stewart, Robert

H. Huguet.

Charles Brute’ de Remur, Vicaire of

Dol de Bretagne in the Department of

He et Vilaine, wrote this year to Dr.

McCaffrey, asking for details of the

life of his grand-uncle, our Father

Brute. Charles tells how his cousin, a

Benedictine named Jaussions, had come

to this country, and visited this

place as well as Vincennes, and

collected material, but " had died

when about returning to France. All

his notes were destroyed in a fire at

Vincennes."In reference to this,

Father Oster, pastor of Vincennes,

wrote December 5, 1907, that he had

ransacked the house and found

absolutely no trace of any papers of

this monk, but that the alleged fire

never occurred. He quotes Prof.

Edwards, of Notre Dame, however, as

saying that Bishop de St. Palais had

at one time burnt a lot of papers as

rubbish, and that the professor had

carried to Notre Dame "some papers

regarding Brute." The nature of the

burnt papers "remains a mystery."

On July 8, 1870, the President was

authorized to take six months'

recreation, and a thousand dollars was

given to help him do so.

On September 12th, Rev. John A.

Watterson, a future president, was

offered the chair of Elementary Moral

Theology. He had been ordained in '67.

August 8, 1870, Father John

Shanahan died in New York, the first

missionary priest to go forth, in

1823, from the Mountain. He labored at

Utica, and was there when the flotilla

bearing Governor Clinton passed on the

newly-opened Erie Canal, which was

illuminated by blazing tar-barrels.

They had left Buffalo on Wednesday

morning and arrived in Utica Sunday

noon. They carried water from Lake

Erie and spilt it into the Atlantic at

Sandy Hook. Father Shanahan naturally

contracted the habit of traveling, and

worked toward the last in California,

but became blind and died in New York.

At the Commencement, June 28, 1871,

the roll showed one hundred and

twenty-nine boys and twenty-nine

seminarians. Seven were graduated, and

the honors of the collegiate classes

were given to Henry C. Semple, Thomas

J. McTighe, John B. Head, Jerome B.

McTighe, Francis C. McGirr, Owen

O'Brien, and W. L. Lemonnier. Charles

J. Reddy was the valedictorian.

In the Old Church on the Hill hung

an ancient crucifix (now in the

chapel) given to Dr. McCaffrey about

1840 at Warrenton, Va., where he had

preached a dedicatory sermon. Over the

head of this figure the light of the

setting sun entered and produced a

deep effect on pious worshipers, who

realized the truth of the overarching

inscription: "Lord, I have loved the

beauty of Thy house and the place

where Thy glory dwelleth."

The Catoctin Clarion, July 9, 1871,

has a legend to the following effect:

"It is whispered among the boys at

Mount St. Mark's that once a poor,

weary stranger had been seen for some

days wandering about the College and

the Convent, those homes of learning

and piety where the turbulent spirits

of boyhood in the one are led

heavenward under the invocation of the

Virgin's name, and the giddy

imaginings of girlhood in the other

are guided into peaceful paths under

the patronage of St. Joseph.

|

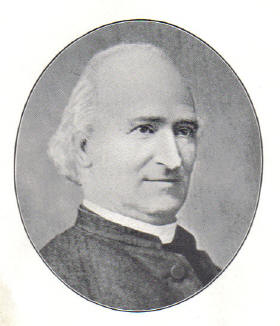

Right Rev. Richard

Gilmour, D.D. Bishop of Cleveland |

"The stranger had also been seen

straying through the long grass of the

Mountain graveyard as if in search of

some treasure buried beneath its waves

of green ; again he had been watched

along the path leading to the Virgin's

Grotto, a shrine up the mountain side,

where a statue of her who is called

Refuge of Sinners stood with hands

outstretched to welcome weary souls.

There he lay prostrate for hours while

the eddying winds swept heaps of

October leaves over his motionless

form as if to hide him from the sight

of men.

"He zealously shunned all

intercourse with the people of the

village or the students, and avoided

all opportunities of being addressed

by the pitying priests who marked his

haggard mien and wretched garb.

"One morning as a procession of

boys wound slowly up to the Mountain

Church, carrying on their breasts the

symbols which betokened the high

privilege they were soon to enjoy of

being admitted to the Table of the

Lord, the poor stranger was seen to

follow, as though intent upon entering

the sacred edifice; but, drawing back

irresolutely as the bays passed in, he

fled up the path towards the lonely

Grotto.

"Perhaps many an earnest prayer was

lifted for him that day, perhaps he

was remembered in the Memento far the

Living when the minister of God's

mercy stood before His altar of

sacrifice and love. But the story runs

that in the afternoon of that bright

day, just as the sun was setting, he

was seen moving toward the doorway of

the Church. At last he crossed the

threshold and hurried with a strange,

wild look towards the silent altar.

The sanctuary lamp burnt steadily

though dim, and the old Spanish

crucifix enfolded in the growing gloom

showed the dead Christ white and

real-like. A look of almost defiant

pleasure stole across the stranger's

face, while a scornful smile gathered

around his lips as he gazed at the

helpless figure whose wounds, to him,

were dropping with unavailing blood.

Suddenly, above the bowed head of the

crucified, a fierce glow spread its

crimson stain upon the white ceiling

of the wall. He raised his hands

appealingly, but the liquid luster

smote the trembling palms. He dropped

his arms, but the crimson stream

poured full upon his breast. He

started to his feet, but his whole

frame seemed flooded in a tide of

blood. With a fearful shriek he sprang

from the denouncing vision, rushed

frantically along the silent nave and

fell at last before a priest whose

pitying heart had led him after the

conscience-stricken sinner in the

church. Here at the feet of one who

has the power to bind and loose, the

stranger told his fearful tale of

suffering and sin, and offered up his

life as atonement for the one that he

had taken.

"The tradition of the College then

relates how he went out of the church

as the sun disappeared behind the

mountain and slowly went his way

towards the Grotto. The rising moon

found him prostrate on the dead leaves

at the statue's feet, but as the

eastern sun flung its beam over the

lovely shrine, the haggard face looked

up towards the sky, while a roseate

tender glow flooded all nature with

its gleam, lighted up, as with a halo,

his raised appealing hands, and then

in a mist of golden light the stranger

passed down the mountain side into the

peaceful valley, to return no more.

"But when a few months later the

College fathers bade the students

remember in their prayers a poor

criminal who having voluntarily given

himself up to justice, and thereby

restored liberty and life to one

accused wrongfully of his own dark

sin, was to suffer the death penalty

that day at set of sun in one of the

distant cities of the state, the ever

sympathetic hearts of boyhood recalled

the wayward stranger. But most vivid

was the recollection and most earnest

were the supplications there in the

lonely Grotto all shrouded with the

dead October leaves, where the sweet

face of her who is called the Help of

Christians seemed to look with pity on

her clients, and in the Church before

the Crucifix, above whose head still

lay the crimson cloud, but in the

center of which there palpitated a

softer flush which touched all

beholders as tho' a trembling heart

was there appealing for God's mercy

and men's prayers.

"Thus ends the American legend,

beautiful with the memory of October

leaves, and touching in its

recollections of the grand old

Mountain Church. How eloquently and

how solemnly that light over the altar

spoke to the young worshipers of God's

mercy to poor repentant sinners; and

how their elders realized with

grateful hearts how small sometimes

are the means He deigns to use to

bring the prodigal son once more to

His loving arms!"

Prof. Beleke after teaching at the

Mountain for twenty-five years had

established in Chicago a costly and

flourishing College. With its

outbuildings, library, etc., it was

destroyed in the great fire this year.

Dr. McCaffrey being absent from the

College in Jane, Father John

McCloskey, the Vice-President, writes

him Jane 15,1872:

"Rev. and dear Friend: Between the

great Mechanicstown (Thurmont) Fair

and the examination which followed

immediately, I have been kept so busy

that I could not write.

"The Fair was a complete success,

but another day would have used me up.

Just imagine Anthony McBride, whom I

drafted into the service, and myself

reaching the College between 2 and 3

o'c. in the morning during the whole

week! [This fair was probably to pay

for the Church there. An oil portrait

of Father John was raffled at this

Cur; it was taken to Ohio and found

its way back to the Collegein 1907.]

"The examinations are pretty well

ahead ; but the preparations for the

grand finale are beginning to stare us

in the face and make us anxious about

our position. Wfll you be with us? We

all hope you will: but should the

state of your health make it doubtful,

let us know; and if I am to try to

fill your place on the 26th, I would

like you to give me an idea of what I

am to say about your absence we still

cherish the hope that you will be with

us on that day. . ."

The facts are that on April 26,

1872, Dr. McCaffrey, on account of

failing health, had resigned the

office he had held since March 17,

1838, but this resignation was not to

be announced till commencement. It was

resolved that the resignation be

accepted, but that he was to be

considered a member of the Council and

of the house; his room to be kept for

him always, and this to be still his

home. His usual salary of a thousand

dollars was continued and the grant

previously made of a thousand dollars

was confirmed, and the "Council hopes

that he will not hesitate to draw for

this or a further amount as occasion

may require."

On June 3, Rev. W. J. Hill entered

the Faculty as Professor of

Mathematics, and on Nov. 22, Rev. John

McCloskey was elected President,

Treasurer and Prefect of Studies;

Father McMurdie, Vice-president and

Father Watterson, Secretary.

At the Commencement in June '72

there were six graduates, out of one

hundred forty boys and thirty-two

seminarians. The valedictorian was

Thomas M. Compton, and the honors went

to Thomas J. McTighe, John B. Head,

Francis C. McGirr, Isaac H. Stauffer,

John J. Negrotto, Thomas F. Reilly,

Elton G. Zimmermann.

Dr. McCaffrey now became "President

Emeritus, "and Father John, a resident

of the College from 1830, when he

entered it a boy of thirteen, and it’s

a Vice-President and Treasurer since

1840, now was in a position to carry

out his ideas, and, the historian

says," speedily infused a new life and

spirit into the institution,"

enforcing also attention to dress,

carriage and general deportment.

Our readers will be pleased with

some reminiscences of a grad. of '72,

himself one of the most loving and

lovable as well as brilliant of the

sons of Alma Mater. We select some

paragraphs from a letter to the

Mountaineer.

"It really seems but a little

while, however, since I first dropped

into college life, making a

disgraceful entree by falling out of

the rickety old contrivance then known

as the Gettysburg stage, after a

bitterly cold ride of thirteen miles

over that never-to-be-forgotten trail,

in March, 1868.

"The first evening we went into

supper to indulge in that

indescribable concoction of old Hyson

then fashionable with the cook. I can

smell it yet. After grace, Fenian

received the customary manual

applause. I could not make it out, and

asked him (he had my ' loaf) what it

was all about. He said, "About you, of

course; why won't you get up and make

your bow?" I did so at once, and the

uproar can be imagined but not

described. My coach laughed over my

discomfiture till the tears rolled

down his cheeks. . . .

"I will briefly sketch the College

as it was then and for some years

after, in order that readers of the

Mountaineer, who are of a complaining

temper, may have some food for

thought.

"The buildings were about as they

are now in the general make-up. The

poor old log 'White House' on the

front terrace was occupied, in the

basement by the ‘gunjer shop.' shoe

shop and carpenter shop; on the first

floor, by the college office and

stationery department and one of the

priests; on the second floor, by

several professors and the

vice-president; and on the top floor,

by a battalion of College

supernumeraries, among them, I

believe, Lee Spalding. A billiard-room

was an abomination not to be thought

of. The reading-room was only half its

present length, the front half being

the 'jug room.' The present box-rooms

underneath were the ' big' and '

little' play rooms, and were kept

clear of all such impedimenta as are

to be found there now. In those days

the recipient of a box from home

either disposed of it at once with the

help of his friends, or had to mount

guard over it, and even then a 'flying

wedge' would be put in motion to his

undoing and the annihilation of his

box.

|

Rev. John McCloskey

D.D. Eighth and Tenth President |

"The bowling-alley was back of the

study hall, and, while by no means in

a state of innocuous desuetude, was

hardly to be considered a prize-winner

for elegance. I understood it had been

constructed about twelve years before

by a carpenter who was afflicted with

strabismus and used a home made level,

laying the boards flat wise. The balls

were of a misfit and the pins a

disreputable and disorderly set. It

required genuine skill to make good

scores on that alley, but very

handsome totals were made daily, and

the alley was in good demand on cold

days. . . .

"The winters were very cold, the

mercury frequently going many degrees

below zero, and snow lying for many

weeks without a thaw. The study hall

had one large stove, and the

class-room passage one small stove

situated in its middle. Each play-room

had one old-fashioned egg-stove. The

dormitory was bleak and cold, no

carpet nor rugs, no stove of any kind,

and two oil lamps. Cold as language

can be, it is not chilly enough to

describe the hardships we endured in

those essentials of education the

study hall, class-room and dormitory.

Most of the boys had the old-time

men's-shawls, which they wore in study

and class, and at night folded several

times and laid over the bed-clothes. I

can truthfully say to the boys now at

the dear old place, that they have a

soft snap in respect to comforts and

privileges, compared to the hardships

of those days.

"The gymnasium was a roomy affair,

composed of a few instruments of

torture out in the open air on the

front terrace, roofed over in later

years. A flying horse, trapeze, two

pairs of rings, a pair of shoulder

poles, two ladders, a pair of

parallel-bars, and a few unmatched

dumb-bells constituted the outfit. I

designed a few additions which, after

much persistence, were ordered and

finally constructed. The old open-air

gymnasium was the source of a vast

amount of jolly fun. All sorts of

matches were made and decided

sometimes on their merits, but not

unfrequently by a test of capacity for

the production of gore, with a warm

handshake for the windup.

"I shall never forget an exploit of

my own on the tan-bark. One vacation I

witnessed a gymnastic exhibition; and

when I saw a double somersault thrown

from a trapeze, I determined I would

learn the trick when I got back to the

Mountain. Day after day I went to the

Gymnasium ; day after day I would work

up a tremendous swing on the trapeze,

and day after day I quit because I

positively could not let go of the bar

when I got up to the dizzy level

necessary for the double turn. Thus

all September passed.

"Finally in October a fresh lot of

bark was spread, and I took courage

and foolishly made public my intention

to do or die the following Sunday,

before dinner. The day and the hour

came around; I was on the spot and so

were thirty or forty of the boys. I

swung up and up to almost a level and

stopped again to think, to the disgust

of the whole crowd. I must do it

somehow, but how? It is one of those

tricks one cannot learn by degrees,

for there is no comfortable spot to

alight on between one complete turn

and two. Well, up I went again. The

boys began an exasperating sort of

rhythmic groaning, keeping time to the

swings of the trapeze. At last with a

tremendous wriggle I let go. I have

never been quite sure whether I turned

eleven or thirteen times before

hitting. My chum assured me I turned

exactly one and thirty-nine

one-hundredths time, and therein lay

disaster. My nose ploughed up the

tan-bark in realistic fashion, and I

was earned to the fountain to cool

off, and thence to the infirmary. That

was about twenty years ago, and to

this day I hare not mastered the

double turn. One real earnest trial

was enough.

"As to privileges in those days,

they were unknown. The use of tobacco

was positively prohibited. The whole

corps of prefects and teachers seemed

to resolve itself into a detective

bureau. It was bad policy, I think,

but there h was; and not a day passed

but some one was punished. A hundred

lines of Virgil to memorize by

Thursday was a terrible burden to a

boy booked for a ball match that day,

for unless he could recite correctly

he had to remain in 'jug' all day. A

thousand lines of ancient history to

write was a very common penalty. And

these rules were for all alike, not

being relaxed for even the grown men

attending the College. Still greater

disaster often befell, for tobacco was

contraband, and its discovery in

whatever form was immediately followed

by confiscation.

"The lower terrace was 'out of

bounds;' so was the back upper

terrace. Raids were constantly being

attempted. Deficiency appropriations

would be made by a party of boys, one

selected as raider, and for weeks

would he watch for the opportunity to

slip down to Mrs. Burke's, and then,

harder yet, to steer his cargo into

haven without being wrecked and

looted. Scylla and Charybdis would

have no terrors for our raiders of

those days.

"Besides bowling and hand-ball, our

games were baseball and 'shinny,'

according to season. All practice

games of ball were on the terrace, and

in fact most match games. There was

little inducement to go to the field.

For two years we had an open space at

a distance straight out from the

College of more than a mile. Later we

had a fallow field a furlong nearer,

but not fit to play in. We had no real

encouragement from the Faculty of the

College.

"All sports were looked upon as

obstacles to learning, and were in

consequence frowned upon. They were

not openly condemned, it is true, but

there was no approval, no incitement

to excellence; and yet I often think

that because of that very fact and the

perversity of human nature, more

enthusiasm existed among the players

than would have been the case under a

liberal and fostering regime. And that

very enthusiasm, with the incessant

practice it engendered, gave us many

fine ball players.

"The first year a costume was

permitted we were a sight. Knee

breeches would not be tolerated, and

we had to appear the day after ' Exi'

in Baltimore in a clumsy

country-bumpkin rig of long trousers.

The contrast with our opponents' neat

suits was mortifying, and we were

unmercifully guyed.

"Occasionally a fad would spring up

for some special amusement, live a few

weeks of feverish existence and then

die out. 'Marbles' was one of these.

Sometimes the center ring for marble

stakes, and again, ' holes' for bare

knuckle stakes. On a cold day, in a

six or eight-handed game, the

unfortunate loser had a hard time of

it. One year marble playing took this

form. We would stand on the back porch

and shoot up at a knot-hole, the idea

being to make a bull's-eye. I believe

that knot-hole is visible to-day ; and

unless the interior of the structure

has been looted years ago, it must

contain a motley treasure of marbles,

'glassies,' 'white-alleys,'

'blood-alleys,' etc.

"A weekly episode of those times

was the charge of the gunjer brigade.

We all had the princely credit of

fifteen cents per week, but it was all

according to the modern principles of

the ''country store." We could not get

the cash, but we would take it out in

trade at the College delicatessen

establishment, wherein were arranged

once a week a limited assortment

composed of 'gunjers' (ginger cakes)

and beautiful barber-pole candy. Like

Wanamaker's, it was a one-price store,

positively no rebates or discounts,

and no goods taken back. Talk about

your teams 'lining up' nowadays ! It

is nothing to what then occurred every

Friday on the tap of the four o'clock

bell. The line formed with a rash,

extending away out on the terrace; the

head of the line would pass in his hat

to the majestic goddess who presided,

indicated his choice as ' ten gunjers

and five candy,' or whatever else his

palate craved, receive back his hat

and then religiously go through the

ordeal which awaited all alike. Custom

had somehow gradually crystallized a

mere courtesy into a law unwritten,

but binding in an extraordinary

degree. The handful of cakes and candy

had to be carried down the line and

held in passing for each boy to help

himself if he chose. Of course none

ever did so, except in the case of an

intimate friend's being pressed to

take some, but the pilgrimage was made

regularly. Now and then a hungry

fellow would make off out of reach of

the line, or a selfish boy would pass

down the line on a trot, holding his

hat, but his train was usually an

express which made no stops.

Occasionally some chap would get

obstreperous near the head of the line

or try to dodge in ahead. Instantly

would come the cry, ' pass him down,'

and the whole would at once bear a

hand, and his initial velocity would

be forcibly maintained till he shot

past the end to make n new start.

After this weekly distribution supreme

contentment spread her wings over the

College for a full half hour, and the

blissful silence was disturbed only by

the ravenous munching of the gunjers

and the crunching of toothsome sticks.

Once or twice in my time, the gunjer

shop was burglarized and cakes and

candy disappeared. Whether these

disasters were precipitated by college

boys or tramps, 'I dinna ken, but

hae me doots.'

"It must be remembered that

privileges were so seldom granted that

when they fell to our lot we had a

keen appreciation of them, and I

believe the enjoyment was

proportionately intense. For example,

in the refectory we very seldom got '

talk,' except occasionally at Sunday

breakfast and Thursday dinner. Let any

pretence for talk arise, such as a

stranger at the table, a first snow

storm, special news from the outer

world, or any of a dozen possible

reasons, and every neck in the

refectory would be craned for the

signal to the reader to 'come down.'

What a jolly meal then always

followed! Growls from the grumblers

were unheard and satisfaction reigned

supreme.

"Another privilege was that granted

the brass band on Christmas. We were

quietly aroused about three o'clock in

the morning, got up, dressed and

washed, got our instruments, and then

tip-toed up to the dormitory door,

where, at the signal from good old Dr.

Dielman, we thundered forth the

glorious strains of the 'Adeste

Fideles.' This was always a thrilling

scene, and aroused boundless

enthusiasm. After prayers in the study

hall, we repeated. Then came the march

up the hill to Christmas Mass, at

which the band played 'Adeste' several

times. It can be easily understood

that the band was pretty dry by that

time. After reaching the terrace we

would get a call to Father McCloskey's

room in the White House, where, after

an elaborate speech of compliment and

welcome, and after listening to the

same old jokes about blowing our own

horn and wetting our whistles, we got

each a mug of alleged eggnog. The egg

was there certainly, and the nutmeg

and the water, but the eggnog was

undiscoverable. Colonel Blank, of

Kentucky, would have considered it an

attempt to assassinate him in cold

blood. But we enjoyed the situation

because it was a privilege, and the

word in those days was magical.

"But since those days of

comparative severity a new spirit has

been infused into the College a belief

in the wisdom of making boys

comfortable, a strong and hearty

encouragement to athletic sports, a

liberality in according personal

privileges ; and this spirit allowed

to sway the college destinies through

its present Faculty for a few years

longer will, with the substantial help

surely to be given, place the dear old

Mountain at last on the pinnacle which

has always been in sight but now only

coming within reach.

"With steam heat, electric light,

and a modem gymnasium, the traditional

glories of the days before the war

will be hers again and more. For with

all these changes comes a softening

influence over the stubborn spirit of

the rebellious and discontented,

harmony takes the place of turbulence

and discord, the compulsory student

becomes unknown, and the whole term is

occupied in a peaceful but

enthusiastic contest for the honors of

the College honors in physical as well

as mental and moral rank and

excellence.

"Thomas McTighe '72."

Dec. 5, 1370. During High Mass a

fire broke oat an the roof of the

Old Church on the Hill, and Prof.

Lagarde and Thomas Metighe '72 had

the delightful task, envied by all

the students, of extinguishing it

with water brought all the way from

the Grotto. While some volunteers

were poking at the stovepipe orifice

from below, "Tom" tore away shingles

from above and poured the water down

on his helpers within, to their

great discomfort but to the intense

amusement of the boys.

Rev. Richard Gilmour '50 became

Bishop of Cleveland, April 14, 1872.

While these things were passing

at the Mountain, there died, January

23, 1873, at St. Louis, Rev. John F.

McGerry, C. M., third President of

the College. He was also first

President of the New York College at

Nyack, and later pastor in

Rochester, X. Y. In 1840 he joined

the Lazarists, who were commencing

at the Barrens, Mo. Father McGerry

was born in Maryland, November 17,

1796, of Revolutionary stock.

The name of Thomas Fitzgerald, of

Brooklyn, N. Y., who was destined to

do great service to the College,

appears among the prefects of

1872-3.

Chapter 56

|

Chapter Index

Special thanks to John Miller for his efforts in scanning the book's contents and converting it into the web page you are now viewing.

|